cookblog |

| Foster Child Of Silence And Slow Time Posted: 28 Sep 2011 11:59 AM PDT Last winter I wrote a post about my first attempts at making vinegar. I set a few types in motion on the kitchen counter, and over the course of the winter I added several more. Now, at the six-or-so month mark, I thought it would be helpful to check in on their progress to see how the different kinds have fermented, aged, and matured in that time. Given that it’s cider season, I’m eager to bottle as many of these as I can to make room for the next batches.

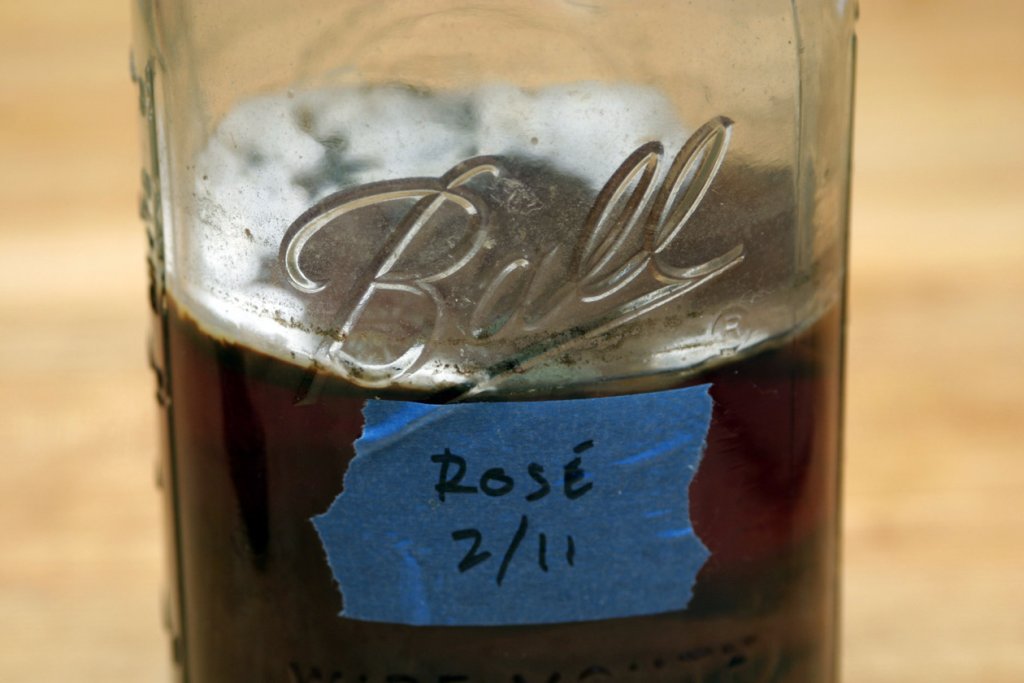

The gallon of apple cider is wonderful. If you’re at all interested in making vinegar, start with local, organic cider: buy half a gallon, pour it into a glass jar, cover the opening with cheesecloth and a rubber band (to keep flies out) and let it sit on the counter out of direct sunlight. Unlike pickles and wine, it likes heat; if your body is comfortable, it will be. What happens is that yeasts will colonize the cider and ferment all that sugar into alcohol until you have a hard, dry cider. At that point, acetobacteria will take over, metabolizing the alcohol into acetic acid, which is vinegar. All these other versions are just as easy, but represent slightly higher risks of failure. I’ve never had (organic) cider not turn into great vinegar. It will also provide you with abundant mother, with which you can jump-start other varieties. Adding some cider and mother helps give recalcitrant liquids the boost they need to undergo the desired transformation. Check out my giant cider mother that grew in the gallon jar. It’s an inch thick and feels like firm rubber: And organic really matters. I’ve had a few conversations with other vinegar geeks, and my unscientific survey seems to indicate that crops sprayed with unknown toxins can have a major negative effect on the natural processes that lead to vinegar. It’s a startling illustration of the potent and invisible pesticides that cover so much of the food in the world today. Use organic cider, wine, and other things. For example, the rosé vinegar that I started at the same time as the red is a moldy mess and will be thrown out. I used cheap-ass Spanish wine and clearly it had something in it which impeded the bacteria from doing their thing, allowing mold to take over. For the next batch I will use organic wine. It’s easy to tell the difference between mold and a healthy vinegar mother; the former is hairy and looks like mold and the latter is a milky disc that floats on the surface and slowly thickens. Poke it down from time to time to make sure the liquid gets enough oxygen. Here’s the moldy rosé: The maple is getting exciting, and I am duly excited by it. This was made from sap I got from a friend, the same source from which we made all the syrup back in March. I reduced the sap until it had approximately the sweetness of cider, and then added some mother and let it sit. I figured that the same process would take place, and it appears that I was right. There’s a delicate maple flavor under the sharp acidity that will work well in subtle dishes. It’s fully ready after six months, as is the new batch of black currant that I made using minimally treated juice from Connecticut. Like cider, this has worked for me every time. Back in May, I went spruce-happy and I’ve written a few posts about all the things I did with those bright green tips. For vinegar, because I found the aroma so captivating, I tried two methods. The first involved steeping a quart jar full of tips in vodka, then diluting it to wine strength (about 10 percent) and adding mother. The other batch involved simmering the spruce in cider, then letting it do its normal thing. They’re both sprucey; the plain version has more of the resinous conifer quality and the cider jar has a strong underlying apple sweetness to the flavor (even though there’s no more sugar in it; one of the miracles of cider vinegar is that residual sweet apple flavor that hovers over powerful acidity). After some tasting, I made a blend of maple and both spruces, bottling some and leaving the rest to ferment some more. It’s quite good, with an elegant complexity that I hope will deepen with more age. The red, made mostly from some not inexpensive Australian wine that I bought back at the very beginning of my serious wine-buying and can no longer tolerate, is coming along but has not arrived, even after seven months. There’s no hard and fast formula for aging; as Brother Victor-Antoine, my inspiration to begin all this alchemy, told me last year: “when it tastes like vinegar, it’s vinegar.” The red needs more time. The lilac, made by simmering flowers in cider like the spruce, is also ready, but is not as floral as I wanted it to be. I may add a few spritzes of rosewater to emphasize that quality. Once these are in bottle, it will be time to start new versions. I have to go pick sumac this week; the maple-sumac from last year is OK, but needs tinkering. Tune in come spring to see how that works out. Now having this much vinegar on hand might seem insane, but hear me out. I hardly buy citrus any more; the spruce and sumac in particular substitute well for lime and blood orange respectively. And I use vinegar of one sort or another in almost everything I cook these days; like bitterness, I find sourness to be an under-appreciated flavor, which, used judiciously, enhances other flavors and makes food taste better by balancing all five tastes. Acidic wine is good with food, and acidic food is good with or without wine. Real vinegar is a living, vital food that makes flavors pop and is good for you to boot. It’s also the single easiest artisanal product in the world, since it basically makes itself. That’s all you need to know. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from cookblog To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google Inc., 20 West Kinzie, Chicago IL USA 60610 | |

No comments:

Post a Comment